By Colette Perold

The Plastic Worker Organizing Committee (PWOC) was a project of the UE from 1989-1993. It was one of the first major attempts to experiment with new ways of organizing in the manufacturing sector during the anti-union crusades of the 1980s-90s. With worker committees in roughly 100 plastics factories, PWOC built more than 12 regional committees over its lifespan to coordinate campaigns and build solidarity across the plastics industry.

While PWOC fell short of its ultimate goal of unionizing large swathes of the plastics sector, it had many wins along the way, and produced lessons that rank-and-file and militant unionists would be wise to study closely.

The impetus for building PWOC came from two core places. On one end, the late 1980s to early 1990s was the time when U.S. manufacturing most rapidly moved overseas and to the U.S. South where labor protections were weaker. At the same time, U.S. industry was shifting from manufacturing goods with metals to plastics. This meant that plastics was a growing sector, and plastics factories were sprouting up in areas where UE had either a strong union presence already, or had recently lost members due to factory closures.

With worker committees in roughly 100 plastics factories, PWOC built more than 12 regional committees over its lifespan to coordinate campaigns and build solidarity across the plastics industry.

The idea to build PWOC therefore had three primary goals: (1) to rebuild the UE’s presence in the manufacturing sector, (2) to do so strategically, in an area of industrial growth, and (3) to innovate new organizing models to address the crisis faced by organized labor beginning in the mid-1970s.

The initial plan was ambitious: to organize worker committees across the plastics sector one region at a time. In Erie, Pennsylvania, specifically, the goal was to lead to a general strike for a “master contract” across several factories at once. This militant, multi-shop, region-wide strategy, was approved for funding by a vote of UE members with the support of the UE’s top leadership.

Geographically, PWOC ultimately developed a presence in six areas: Los Angeles; Chicago; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Erie, Pennsylvania with a smaller presence in Philadelphia; across Indiana; and in southern Ohio. On three occasions in PWOC’s four-year span, regional committees elected delegates to gather in Pittsburgh to strategize with other unionized plastics workers.

The combination of these three layers of worker organization — at the factory level, the regional, and the national — helped workers build the class consciousness they needed to carry forward their industry-wide pre-majority organizing.

The PWOC model drew inspiration from the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) of the early 1930s and its predecessor organization, the Trade Union Education League (TUEL), of the 1920s. Made up of worker radicals from across the political Left and sponsored, in part, by the Communist Party USA, the TUEL sought to push the AFL (see Overview of Union History, Structure, and Function section) to the Left and away from its anti-solidaristic, craft-union roots. To a lesser degree, it also formed worker committees in areas where there was no union presence. The work of building new industrial unions in workplaces without union representation was carried on more concertedly by TUEL’s successor, TUUL, beginning in 1929.

Workers who were trained by the TUEL and TUUL became the leaders who helped form several well known CIO unions including the UE, the UAW, the Farm Equipment Workers, and others.

The UE saw TUEL and TUUL as a model precisely because of how they were able to scale up with minimal resources: from individual committees across multiple factories to the ultimate founding of major industrial unions. UE organizers who would go on to build the PWOCs held a union-wide reading group to study TUEL/TUUL founder William Z. Foster’s 1937 iconic “What Means a Strike in Steel” as they drafted the initial PWOC strategy. (In April 2022, workers in the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) described Foster’s similar 1936 pamphlet “Organizing Methods in the Steel Industry” as a major source of inspiration for their successful campaign to win the first union election at Amazon.)

It’s worth noting that even throughout PWOC, the UE did not consider this type of organizing a “pre-majority union” strategy. The idea of workers winning campaigns on the shop floor before filing for an NLRB election was always the strategy the UE pursued. Dave Cohen, who came out of the ranks of a UE factory in the Northeast that got offshored and shuttered, was the only full-time UE staff member whose work was dedicated exclusively to PWOC. As he put it in an interview with EWOC, before the PWOC moment “we didn’t think of it as pre-majority unions. You try to get people to raise hell. And then at some point you think you can make a run to an NLRB election, and you do.” In other words, the UE saw NLRB elections as a necessary step, but never the secret ingredient that would turn “workers” into a “union” the way many unions today do. The union was always the workers themselves fighting for justice and building power.

This made expanding on the TUEL/TUUL model a natural fit for the UE. Some of this came from the PWOC planners’ unique interpretation of TUEL and TUUL. “What’s worth talking about,” UE’s then-organizing director Ed Bruno told EWOC, “is that [management in the 1930s] recognized the union at General Electric, General Motors, Westinghouse, Steel, and others, for purposes of grievance representation for the union’s members only” before the unions gained full recognition with the passing of the NLRA. According to Ed, this is a key part of the origin story of the CIO that is often overlooked. “This was unionism on the way to being a majority,” he told EWOC.

While members-only bargaining is not possible under our current legal framework (and there is significant debate about whether it should be), Ed says the same lessons of how TUEL/TUUL organized still apply today.

‘We didn’t think of it as pre-majority unions. You try to get people to raise hell. And then at some point you think you can make a run to an NLRB election, and you do.’

Ed describes how cadres (“or what the academics now call ‘committed cores,’” he added) began forming in 1928, either “resurfacing from the World War I days or established by the political parties” in key factories. These cadres comprised a mix of Communists, “home-grown radicals,” IWW members, or “just troublemakers” who started to network together and share experiences. While they tried to unionize throughout that period, nothing worked, according to Ed, until they won members-only bargaining and could begin competing for members. This network of cadres was a major element of the formation of the CIO. (See Overview of Union History, Structure, and Function).

The success of the TUEL/TUUL cadre model is what led Ed and the rest of the PWOC architects to devise a concept Ed calls “sweep” elections. This is what they put to the test with PWOC.

The concept of “sweep elections” involves connecting committed cores, or cadres, across workplaces, going public with that network early on, and strengthening that network until reaching a “breakthrough” in one workplace that catches on at the others. The goal is to achieve union recognition and bargaining at several workplaces at the same time.

One of the key ingredients to a successful sweep election is what Ed calls the “calling card” issue. This means finding one major worker issue that (1) all workers can connect with, and (2) connects workers’ workplace concerns with broader issues of citizenship outside of work. Examples of “calling card” issues Ed gives are, for nurses, nurse-to-patient ratios, and for workers during the early days of the U.S. labor movement, a shorter workweek combined with the right to public education.

The goal in sweep elections is to achieve union recognition and bargaining at several workplaces at the same time.

Another way to understand connecting workplace issues to those of citizenship is that, when you’re doing it, you are buttressing your Section 7 rights (the right to organize with your coworkers at work) with your constitutional First Amendment rights (to speak and to assemble in public). “It’s a lot safer for a workplace to be out on the street,” says Ed.

With the right calling-card issue identified, Ed says that the most successful sweep elections move from the shop-floor to the public arena very quickly. This both empowers workers and protects them. In a sweep-election strategy, those that go “too deep” in one individual workplace end up failing, he says, because they get too caught up in their own workplaces and lose sight of the broader movement.

‘It’s a lot safer for a workplace to be out on the street.’

What you’re ultimately aiming for are “breakthroughs” that catch fire, not unlike the initial Starbucks organizing drive in Buffalo, NY. One of the greatest examples of a “breakthrough,” according to Ed, is the one that gave us the modern labor movement: When workers won a contract for their members at the famous sit-down strike of 1936-7 at General Motors in Flint, Michigan, they inspired 477 more sit-down strikes involving over 500,000 workers the following year. With that, millions of workers formed unions, flooding into both the CIO and the AFL.

According to Ed, none of this would have happened without the network of cadres.

After developing the concept of “sweep elections” with PWOC, Ed expanded on it to build unions in the south, including the first ever recognized nurses union in Texas. It is now a core concept used in the Southern Workers Assembly — one of the most vibrant efforts to organize workers in the South today.

In terms of its geographic spread, the majority of PWOC activity was concentrated in four areas: greater Los Angeles, where there were around a thousand plastics factories; the Milwaukee–Chicago manufacturing corridor; Erie, Pennsylvania; and southern Ohio. The decision to focus on these four areas came from two places: (1) A research process that assessed where the plastics industry was concentrated in the country; (2) A strategic assessment of where UE membership was concentrated or where UE already had existing membership in plastics factories. Erie was one of the cities that best exemplified both. At the time it was one of the most industrialized cities in the U.S., and the UE represented workers at the big General Electric locomotive factory. The idea in Erie specifically was to build committees across 50 factories at once.

UE first made contact with plastics workers in a highly public way: by doing flyering blitzes. For example, in Erie, PA they would flyer for three to four days at a time, with blitzes involving local UE members, around 20 UE staff members, and around 25 college students, several of whom were affiliated with nearby DSA chapters. With a list of 60 target factories in the greater Erie area, these workers, organizers, and activists sought to establish contacts across different shifts at as many factories as possible.

Once the UE had established contacts, building committees to organize workers around their issues was the next step. One of their main strategies was training workers in how to exercise their NLRA Section 7 rights. This meant using all the tools legally available under the NLRA to take collective action as non-unionized workers to fight injustice on the factory floor.

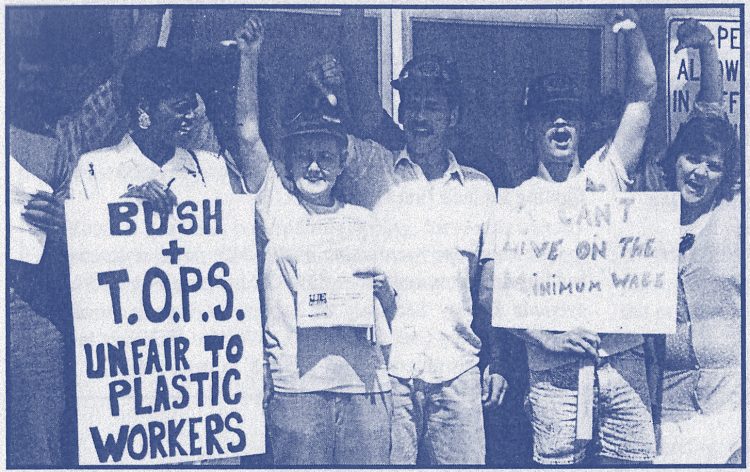

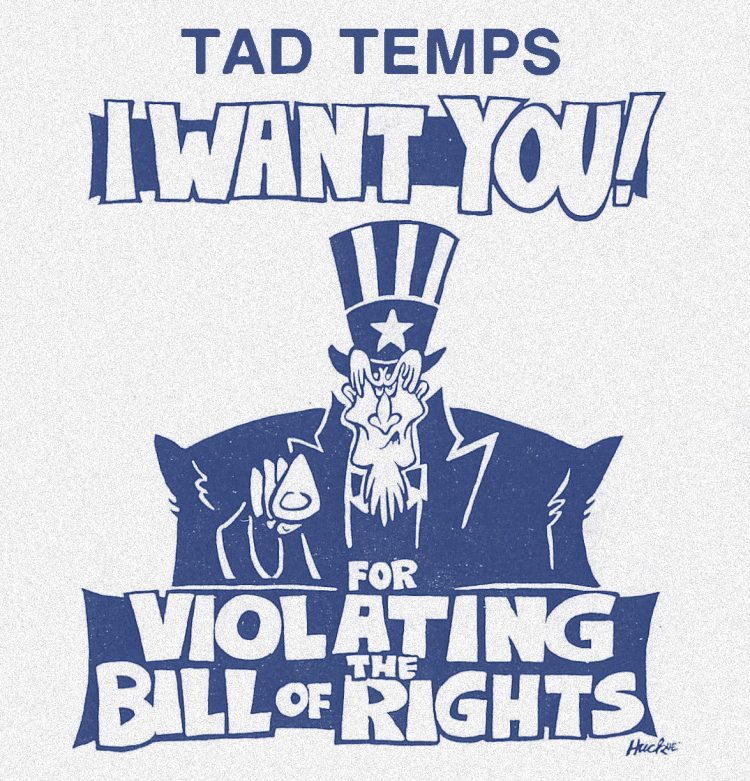

One of the most memorable campaigns for PWOC members in Erie, Pennsylvania, where PWOC had committees in 15 factories, came when the major temp agencies in the area that contracted with local plants started telling temp workers they were forbidden to unionize by law. Fearing the growing labor unrest in plastics factories, temp agencies were doing whatever they could to stifle PWOC’s organizing so as not to risk their contracting relationships with local plants. Tad Temporaries, one of the largest temp agencies in Erie, issued a statement explaining that “plastics union organizers are putting on a strong push to organize all plastics shops,” falsely claiming that temporary workers could not legally “participate in voting” for a union, or in “any discussion thereof of union business” in the U.S.

In response, the day before July 4, 75 plastics workers — led by a (particularly tall) UE field organizer, Peter Knowlton, dressed as Uncle Sam — picketed the Tad offices, chanting: “We Want Democracy, Not Hypocrisy!” From there, Uncle Sam and six other workers marched into Tad’s office with reporters from three local news stations and delivered a copy of the Bill of Rights, along with a letter from PWOC, which Uncle Sam then read: “Your notice telling employees that they cannot participate in any discussion of union business,” it said, “not only violates national labor law, but also the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution.”

With the message clearly registering, workers then took turns educating Tad officials about their right to organize. Tad officials got visibly nervous and quickly conceded their error. Workers demanded Tad put a correction in writing, and soon after Tad circulated a second notice to temp workers correcting the first and clarifying the workers’ right to organize. Their win in forcing Tad to backtrack and fess up was extremely empowering for the temp workers involved.

PWOC members counted 100 factories across the country that implemented the raise in response to their organizing.

Other tactics PWOC used included pickets, marches, and community events. In one march, campaigns had built so much power that 50 workers took their march straight through the factory. Picnics and other social events in which workers had the chance to tell their stories and connect over common workplace struggles was crucial to their building trust in one another. PWOC’s largest events exceeded 500 workers. At one, PWOC members connected their workplace issues with those of basic citizenship in “sweep-election” style, rallying for National Health Care. Petitions for their National Health Care campaigns garnered several thousand signatures each. PWOC members also regularly joined the picket lines of sister and brother unions nearby.

One of their biggest wins was in response to a coordinated campaign for $1 per hour raises across the plastics sector. After three months of the campaign, PWOC members counted 100 factories across the country that implemented the raise in response to their organizing.

As part of their larger strategy to build the union through militant struggle before jumping to NLRB elections, PWOC innovated a tactic they called “Community Elections” in which they staged their own union elections without seeking governmental certification or company recognition per se. (The Community Election model was later pitched to Jobs with Justice, becoming the “Workers Rights Boards.”) Though partially symbolic, these Community Elections had a major impact on the plastics worker organizing.

PWOC ran their Community Elections as systematically as the UE runs NLRB elections. Support on the shop floor was assessed by having workers sign pledge cards or show their union pride publicly with union t-shirts, stickers, or buttons. PWOC committee members tracked their support closely, with detailed worker information listing who was a strong supporter, weak supporter, undecided, or anti-union. (Sometimes they used a numbering system the way many unions do today, but they insisted on keeping written evaluations of workers to discourage what Dave Cohen calls a “static view of people” making it harder to assess when and where support shifts given changing conditions in the workplace.)

When the numbers showed a majority of workers in support of the union, the committee would recruit a well known community leader like a pastor or congressperson’s chief aide to oversee the election, and then announce it.

While the workers usually knew that management would not want to join in the election, they sent a worker delegation to invite the company anyway. To them, this legitimized their process while also flexing their muscles and calling management’s bluff. From there, they’d run publicity in the local press announcing the election. As PWOC staffer Dave Cohen told EWOC, if workers were going to take bold action like this, they needed to be as “out in the open” as possible.

In addition to their careful analysis of shop-floor union support, PWOC made sure to check two other crucial boxes in their election organizing. First, they made sure their lists included the full names of management and every boss in the factory. The one time they did not confirm their list enough times was the only Community Election they lost. In this one case, management turned out bosses to vote, and since the lists were inaccurate, the election overseer did not have enough information to refuse the bosses a vote. (Unfortunately this one had a high-profile election overseer: a congressman’s chief aide.)

Once the workers won their Community Election, they felt a stronger sense of being part of a union. From there, going into an NLRB election felt to them more like defending a union rather than waiting to see if they had support.

After that one Community Election loss, PWOC created a system in which anyone who claimed to work at the factory but whose name was not on the list wanted to vote, the election overseer would put their ballot in a separate envelope labeled “to be determined later.” As with NLRB elections, these votes were then consulted if the election results were close enough that the “to be determined later” ballots could shape the outcome.

Another central element of the Community Elections was making sure to turn out every single worker to vote, even those they knew would vote against the union. They did this because in the few factories where they did not turn out the “no-votes,” the workers across the factory ended up questioning the validity of the vote. Having a transparent and equal process was a necessary ingredient for the workers to feel empowered by their election results.

In the end, Community Elections had two major outcomes: a good psychological effect on the workers, and a stronger support base in the cases where the workers did end up pursuing NLRB elections. Like an informal version of the Card Check Neutrality process, workers could run their election as early or late as they wanted to, thereby avoiding the boss’ union busting. The Community Election results therefore felt like the true expression of what workers wanted.

The effect was powerful. Once the workers won their Community Election, they felt a stronger sense of being part of a union. From there, going into an NLRB election felt to them more like defending a union rather than waiting to see if they had support. They won a handful of these NLRB elections this way, and in all the others they lost by much slimmer margins than had been otherwise standard in plastics organizing at the time.

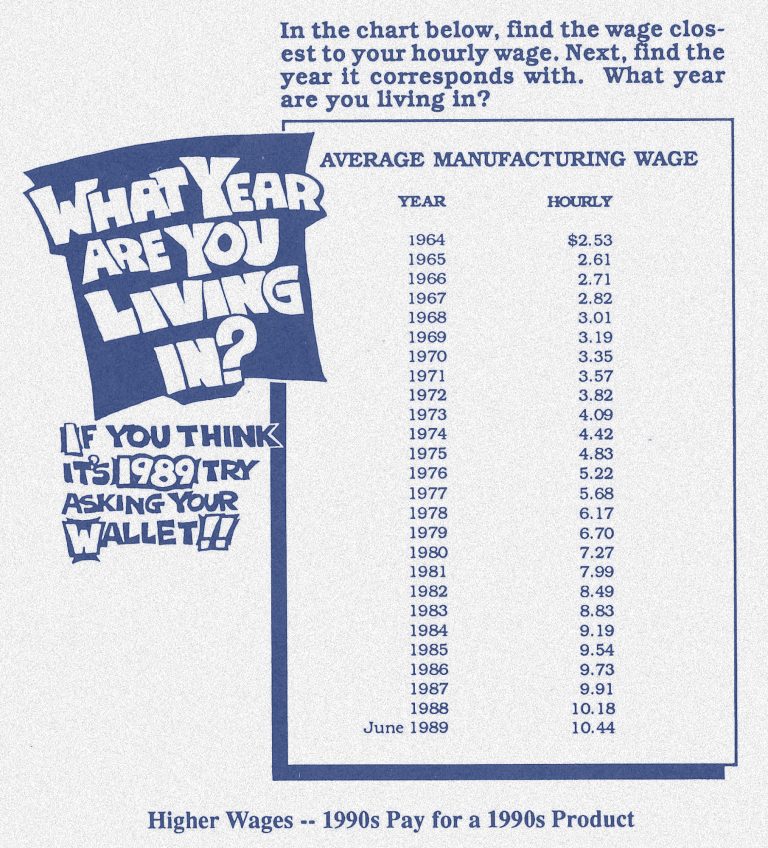

One of the main obstacles PWOC faced in their organizing mirrored the broader trends taking place across the economy. The UE assumed their target areas would be promising to organize because they were all union towns in heavily industrialized areas. But plastics workers in general had such low expectations of their jobs that it was hard to convince them to fight for better conditions. Workers tended to buy into management propaganda that said that plastic labor was as cheap as the new plastics economy itself, regardless of how much money bosses were raking in. In response, PWOC adopted the slogan: “It’s Time.” The slogan contrasted the poor conditions in the plastics factories with the high-tech nature of plastics at a moment when the U.S. was becoming increasingly obsessed with the allure of shiny digital toys.

PWOC organizers found that plastics workers tended to think of their jobs as temporary no matter how long they ended up working in plastics factories. There was always a sense that the best job would come from leaving plastics and getting hired at General Electric or a steel or paper mill — not from improving the conditions at the plastics plants themselves. Dave explained it to EWOC: “People had no holidays, no paid vacation…and were always bouncing back and forth between their job and unemployment checks…they had no expectation of having health insurance. No conceptions of what a pension plan was. They didn’t realize that it was the unions that got those good jobs” at the other plants in the area.

Another obstacle they faced in a handful of plants had to do with the worker committee at the plant ossifying itself as an in-group and losing touch with the sentiment among the workers more broadly.

Another obstacle they faced in a handful of plants had to do with the worker committee at the plant ossifying itself as an in-group and losing touch with the sentiment among the workers more broadly. While this can happen in any union, whether NLRB-recognized or pre-majority, the specific problem PWOC faced was figuring out at what stage to formalize worker committees.

There were differences of opinion on how loose or rigid to build out pre-majority committees within the UE. According to Dave, it was in factories that formalized their committee leadership through elections too quickly that they began to lose the rank and file. In one of the factories with the tightest, most inward-facing committee, a different union succeeded in organizing the workers away from the UE.

‘The steward structure you need when you’re fighting for a union is different from what you need when you have a contract...what we’re looking for is motion. It might not be where you’re at. It might not be militant enough. But you can’t get too ingrained.’

In another, the committee became a clique of all white men who refused to organize with women and Black people, and the UE had to remove them from office for violating the UE constitution.

“The steward structure you need when you’re fighting for a union is different from what you need when you have a contract,” Dave told EWOC. “I always tell people that what we’re looking for is motion. It might not be where you’re at. It might not be militant enough. But you can’t get too ingrained,” he said.

The absence of support from other unions was another obstacle. As UE’s Director of Organization, Ed Bruno went to several unions to pitch them on the PWOC concept, but according to Ed, even the unions who were most enthusiastic about the idea didn’t have organizing departments at the time and couldn’t marshal the resources to put toward this type of slower-build, regional, sweep-election strategy.

A TUEL formation like PWOC would require ongoing union support or the long-term commitment of politicized volunteers, either on the ground or on the shop floor — much like what EWOC is building today — to sustain itself in the long run.

As with several other pre-majority unions, the question of ongoing financial support was a deciding factor in the bulk of the PWOC campaigns coming to a close. Although two or three UE staff members in each core PWOC region were able to dedicate some of their staff time to building PWOC, Dave was the only full-time staffer. After four years the UE — already member-led and less reliant on staff than most unions today — realized the slow nature of the build was draining too much of their already tight pool of resources.

As Dave and past president of UE District 2 Judy Atkins wrote in an article in 2004, a TUEL formation like PWOC would require ongoing union support or the long-term commitment of politicized volunteers, either on the ground or on the shop floor — much like what EWOC is building today — to sustain itself in the long run.

In assessing what he would do differently as the national coordinator of a campaign like PWOC, Dave said he would recommend doing more to cultivate a relationship — however adversarial — with the bosses. “I always tell people,” Dave told EWOC, “that if you want [the bosses] to surrender to you, they have to have someone to talk to in order to surrender to.”

‘If you want [the bosses] to surrender to you, they have to have someone to talk to in order to surrender.’

The best example of a missed opportunity for bargaining took place in the Erie PWOC hub. The Erie PWOCs met with the local Chamber of Commerce which had a plastics council. “We heard through the grapevine later on that they were split 50/50,” Dave told EWOC. “Half [the council] thought they should cut a deal with the union, and the other half, run by one of the biggest companies, wanted to fight to the death.” But PWOC committee leadership and UE staff did not ultimately follow up with the plastics council as much as they should have, says Dave. “With all this pre-majority stuff,” he said, “you have to actually be bargaining as you go.”

‘With all this pre-majority stuff you have to actually be bargaining as you go.’

Ed echoes the same idea. In a pre-majority context you can’t just “make the demand on the employer” and leave it up to the employer to respond, says Ed. “The demand is not the remedy.” Instead, you have to “make the demand to meet to discuss the remedy.”

Ed gives this hypothetical: Workers have a problem and they know how it needs to be fixed. With a problem and a proposed remedy, they now have a “demand.” But rather than just announce the demand, they should try to meet with management as a union about the problem itself. If the workers have enough power, management may meet with them as a union. But in most cases they won’t, because that would be a form of de facto recognizing the union, and most employers won’t do that because of how empowering it can be for the workers.

When management (in all likelihood) refuses to meet with the workers, the workers can start publicizing the refusal. “‘They won’t meet with us!’ So [they] put the question on the question of meeting,” says Ed. “And in certain campaigns you probably could create a whole litany: ‘We raised vacation policy, they refused to meet. We raised this and they refused to meet. We raised that and they refused to meet.’ You want to build the sense,” says Ed, “that the only way we’re going to get these people to meet is to go on strike or change the law — whichever comes first.”

Orienting the organizing toward meeting helps workers learn for themselves how much power they need to build in order to force management to table. This grassroots approach to recognition and negotiation gets to the “whole matter of what collective bargaining really means,” says Ed.

While there are strategic lessons to be learned from the UE’s work on the PWOC campaigns, according to Ed the greatest obstacle to the PWOC’s success was not actually internal to the campaigns. It was structural, rooted in the transformations taking place across the global economy.

The plastics factories with PWOC committees had less capital invested in the plants than did the plastics and other factories producing heavier industrial equipment. This meant they could more easily shutter and move overseas. Plastics workers likely knew this because of their close familial and community contacts in plants with heavier equipment and more specialized processes.

At the same time, the PWOCs were expanding in the four years prior to the ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which received major national attention during the 1992 presidential election. While there aren’t too many reports of plastics companies threatening to move to Mexico if the workers organized — a threat that would have be illegal if used — national attention was being paid to Texan Independent candidate Ross Perot’s famous warning of a “giant sucking sound” of jobs moving to Mexico if NAFTA were implemented. With NAFTA in the headlines, this was one of the most difficult times for factory organizing.

In the years following PWOC’s close, workers in factories with strong PWOC committees but that didn’t win NLRB elections would call the UE saying they were having a particular shop-floor issue and asking for organizing advice. Some even thought the UE was their union already because the PWOC flyering blitzes made them think they already had a union representing them and assumed the flyers were part of an ongoing union battle.

In Erie, Pennsylvania, a few factories with strong PWOC committees won NLRB elections 10 years after PWOC’s close. And in Ohio, plastics workers at one factory ended up successfully striking for recognition.

After thousands of plastics workers were in motion through PWOC for four intense years of struggle, not to mention several successful NLRB elections and many more close calls, PWOC left a lasting legacy across the plastics sector.

These after-effects beg the question: what could longer-term investments in “sweep-election”-style, pre-majority campaigns produce?

Reflecting on PWOC’s four short but mighty years of existence, Ed told EWOC: “It turns out you can’t do a sweep [election] quite that fast.” Despite the PWOC slogan “It’s time,” Ed told EWOC that a joke began circulating among workers and organizers as PWOC closed up: “Well, maybe it wasn’t quite time.” With the (likely empty) threat of moving factories overseas or to the U.S. South, mixed with the low esteem associated with plastics work, it’s clear in hindsight that for PWOC to have been successful, it would have needed longer-term investment and committed volunteer support. But “unions are not good on longer-range things,” Ed told EWOC.

It might now be time for that to change.

Unless otherwise noted, information from this article comes from Judy Atkins and David Cohen’s “A Proposal for a Twenty-first-Century Trade Union Education League; An Attempt to Solve the Crisis of Organizing the Unorganized,” WorkingUSA 7, no.3 (2004) and author interviews with Dave Cohen, Ed Bruno, and Peter Knowlton.