Alphabet Workers Union

By Ike McCreery

The Alphabet Workers Union (AWU) is a wall-to-wall pre-majority union at Alphabet, the multinational tech conglomerate including Google, YouTube, and others. We represent workers from across the company and have engaged in legal recognition fights as well as other majority and minority strategies.

AWU launched January 4, 2021, with 100 mostly full-time workers after years of worker unrest at Google. We have since grown to 1,400 members out of a 150,000-person North American workforce and a 250,000-person global workforce. We are affiliated with Communications Workers of America (CWA).

AWU is a unique example of a wall-to-wall, pre-majority union at an extremely large and powerful corporation and represents the immense opportunity for organizing at megacorporations, especially among headquarters and office staff, as distinct from logistics or service staff.

Background

AWU’s structure evolved through a confluence of historic factors, inside Google, across the tech industry, and in the context of other union efforts.

Activism among white-collar Google workers had been escalating for several years: employee concerns around policies on Google’s social media platform, then worker protests culminating in the cancelation of a drone artificial intelligence contract, then a 20,000-person global walkout protesting sexual harassment, discrimination, and others. Google’s response to worker activism took a harsher turn when it fired five workers at the end of 2019. Many who would become leaders in AWU cite those firings as the moment unionizing became a real possibility.

Contemporaneously, union efforts among blue-collar contractors at Google had been taking hold. In 2016, Google shuttle drivers organized, followed in 2017 by security guards across Silicon Valley. As of this writing, cafeteria workers across Google’s campuses are 90% unionized with UNITE HERE, having seen their first recognition victory in 2019. The first white collar workers at Google to unionize, contractors in Pittsburgh, affiliated with the Steelworkers and won a recognition vote in 2019 and ratified a contract in 2021.

Activism among white-collar Google workers had been escalating for several years, and contemporaneously, union efforts among blue-collar contractors at Google had been taking hold. All the while, the tech industry more broadly had seen a movement of increased worker activism.

All the while, the tech industry more broadly had seen a movement of increased worker activism, driven largely by Tech Workers Coalition (TWC). This movement developed a narrative persona of the “tech worker,” which included both technical workers as well as blue-collar workers working at tech companies. Activism in the adjacent games industry had also been accelerating, as demonstrated by the emergence of Game Workers Unite. When CWA, AWU’s parent union, founded the Campaign to Organize Digital Employees (CODE), they hired a Game Workers Unite organizer to lead the effort.

This white-collar activism, blue-collar unionism, and narrative shift together shaped how the founding AWU members conceived of themselves. They saw themselves as a network of “tech workers,” spread across many of Google’s offices and functions, overrepresentative of white-collar tech workers but aspirationally organizing alongside blue-collar tech workers. Although AWU’s structure felt like a foregone conclusion by the time workers convened in Chicago in December of 2019 to discuss building a union, the framing of that conversation — the “we” of Google workers and the possibility of a union — were profoundly shaped by this historical context. CWA brought to Chicago decades of deep experience organizing wall-to-wall minority unions: at United Campus Workers (profiled in this case study), Texas State Employees Union, and others. All of these factors continue to shape AWU members’ understanding of our union, as well as our theories of power and change.

Launch

After a year of organizing in secret, AWU decided in late 2020 to go public. The focus supercharged our recruitment: in the weeks leading up to launch, our membership grew quickly from a few dozen to well over a hundred.

When we launched, our membership exploded from 200 to 800, then leveled off as the organization tried to catch up to the hypergrowth. Ahead of time, we had developed a plan for contacting and orienting new members, but we were nonetheless unprepared. As members and staff organizers managed the communication and administrative work of going public, we also worked hard to contact, welcome, and train all the new members. To our surprise, many new members simply never responded to our outreach. Over time, we came to believe that many who joined were “ideological members:” workers who believed in unions, wanted to support us financially, but didn’t want to contribute beyond that. When we were able to make contact, we found our pre-majority structure made orientation more difficult but all the more necessary: many new members struggled to understand our structure and strategy at first because it didn’t fit their preconceptions. We learned to fall back on our strengths: a clear story for why AWU is necessary and a strong culture of organizing.

We found our pre-majority structure made orientation more difficult but all the more necessary. We learned to fall back on our strengths: a clear story for why AWU is necessary and a strong culture of organizing.

Wall-to-wall pre-majority strategy

AWU leaders place as much emphasis on AWU’s wall-to-wall structure as on our pre-majority structure and see the two as connected.

The most important reason for choosing the wall-to-wall pre-majority structure is Alphabet’s sheer size and workplace structure. The founders were building off of years of white-collar worker activism at Google, working with the new “tech worker” identity, but scattered across the workforce.

“We chose this structure because we didn’t think we could get 80,000 people in secret … and because we couldn’t come up with a way … to meaningfully divide them up into bite-sized chunks,” says AWU’s organizing chair.* It’s the workplace’s enormous size and densely networked structure, especially among the white-collar staff, that make the wall-to-wall pre-majority structure appealing. Workers collaborate closely across different roles and geographies, and even across different parts of the corporation, so separating off parts of the workforce just isn’t a viable organizing strategy.

Kickstarter United, a wall-to-wall union of 85 which won their majority election in 2020, demonstrates how a heterogeneous workplace, if small enough, can successfully form a majority union. Starbucks Workers United has taken on another massive organizing challenge, but the workforce is relatively standardized and segmented, making organizing store-by-store viable. Even within AWU, these factors have played a role, as our majority victories have come from more segmented parts of the workforce; but for the task of organizing across the entire workforce, something broader was necessary.

It’s the workplace’s enormous size and densely networked structure, especially among the white-collar staff, that make the wall-to-wall pre-majority structure appealing.

When AWU launched, organizers conceived of the project as a minority union, not a pre-majority union.

“I think we did a bad job … when we launched, of communicating minority versus pre-majority, and I think we’ve really suffered for it in the long run. People don’t realize that is the goal,” says Chris Schmidt, former AWU secretary. But that goal has been shaped by AWU’s experience: Parul Koul, AWU president, recounts, “I think the shift to the language of pre-majority happened in part because it gives you a sense of direction about where you’re going, and I think it also happened in part because more of our membership and … industry is also starting to think more concretely in terms of the gains they could have through a formal contract.” Layoffs across the tech industry in 2023 and 2024 and AWU’s experience of recognition victories among some contractor workers (more below) have contributed to that concrete thinking.

Security was a consideration more unique to Alphabet, and illustrates another way of thinking about pre-majority unionism: organizing in public. Google likes to brand itself as an advertising company, but it’s really a surveillance company.

“Organizing at Google means not being secret in effect … Google can monitor everything you say, which means you have to reorient your approach to be security safe with being public,” Schmidt points out.** Organizing in the open, before having a majority, meets this challenge head-on.

There are two other considerations that reinforce the wall-to-wall strategy. The string of blue-collar union victories, the emergence of the first white collar union in 2019, and TWC’s emphasis that “tech workers” include anyone who works in tech, put a focus on a deeply-felt issue across Google’s campuses. Alphabet separates its workforce into two-tiers: full-time employees (“FTEs”), who have access to Google’s world-famous benefits; and temps, vendors, and contractors (“TVCs”), who don’t. AWU’s wall-to-wall structure allows us to have members across both tiers, bringing workers together across the divide and challenging what is seen as “one of the great injustices” of our workplace, as Koul says.

The intent on unionizing wall-to-wall also had a more historical and ideological component. Early leaders knew of the Congress of Industrial Organization’s (CIO) industrial organizing strategy in the 1930s, which played a defining role in US labor’s strongest era in the mid 20th century. They saw parallels between our situation and the industrial situation that confronted the early CIO, when highly-stratified workforces came together to form massive industrial unions, challenging some of the most powerful corporations in human history.

At launch, though, AWU’s structure was met with some consternation among labor commentators. “Collective action at work cannot be disassociated from bargaining power and a union representing .001 [0.1%] of workers has little such power,” wrote one commentator. Organizing.Work ran an article using AWU as an example of what it calls “top-first campaigns,” which, the author claims, prioritize activity at the top of the organization, “while the minutiae of organizing in shops and work groups is treated as an afterthought, or an inevitability once a campaign reaches a certain size.” AWU leadership circulated this article when it ran shortly after our launch, reading it not as a condemnation — the author made some very wrong assumptions about our strategy — but as a warning. For all of the reasons above — historical identity formations, size and structural considerations, security, focus on the two-tier workforce, and inspiration from the CIO’s industrial organizing strategy — we chose this structure despite its drawbacks.

AWU’s early leaders saw parallels between our situation and the industrial situation that confronted the early CIO, when highly-stratified workforces came together to form massive industrial unions, challenging some of the most powerful corporations in human history.

Recruitment and Structure

From the beginning, AWU has strongly emphasized relational recruitment based on existing workplace structures, as is typical among contemporary union organizing. The bulk of organizing happens in organizing committees embedded in two overlapping structures: geographically-focused chapters and organizationally-focused workplace units.

Emphasis on one or the other structure has oscillated as AWU has moved through phases, reacting to moments and experimenting with different strategies. The earliest union organizing was based in the preexisting geographic networks of activists. At launch, we shifted focus to organizing by workplace organization, thinking that those networks were stronger, that workplace issues were more similar, and that we could wield structural power more effectively. We found, though, that geographically-based relationships were too critical, so we switched back to focusing on geographically-based organizing. “I think that organizing by location has been solid as a starter, getting off the ground. … Physical proximity is nice for meetings. … It’s a good structure just to get more momentum,” says AWU’s organizing chair. As prospects for building density within workplace organizations improve, however, there has more recently been renewed focus on organizing by team, with results still to be seen.

From the beginning, AWU has strongly emphasized relational recruitment based on existing workplace structures.

AWU has made use of recruitment strategies beyond relational organizing as well. The networks of the founding full-time workers fail to reach many workers, especially TVCs. AWU has reached those workers through press, social media, mass emails, and surveys, followed by cold calls, one-on-one meetings, and trainings.

“Keep in mind at all times that you’re all one team working together. … Share in each other’s successes constantly, and make every success of every part of the union a success for the whole union.”

Members pay dues at 1% of total compensation. When discussing dues, AWU organizers emphasize the importance of dues as a way of building collective power, with particular emphasis on challenging the very common misunderstanding that our union is a fee-for-service (affectionately referred to as the “vending machine” union model).

While organizing is taken up by workers across the union in chapter- and workplace-unit organizing committees, union-wide structures maintain most of the bureaucratic and other functions of the union: communications, membership, infrastructure, legislative-political, and other committees.

AWU hosts what we call “union days,” online webinars that all union members, and sometimes non-member workers, are encouraged to attend (recordings can be found on our YouTube channel). Topics generally focus on organizing efforts across Alphabet, either ongoing or retrospective. Schmidt emphasizes the importance of these spaces: “Keep in mind at all times that you’re all one team working together. … Share in each other’s successes constantly, and make every success of every part of the union a success for the whole union.”

Strategies and Tactics

Although AWU is a pre-majority union, we have taken a multi-pronged and somewhat ad hoc strategic approach, making use of different strategies and tactics that fit the many heterogeneous situations in which we organize.

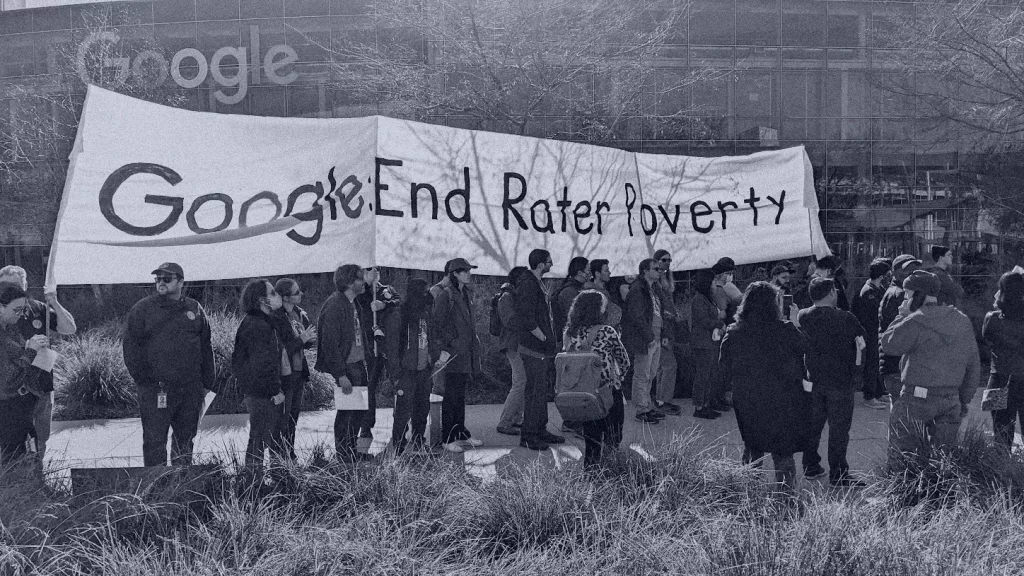

True to our original conception as a minority union, AWU has relied heavily on non-majority tactics to win material victories. A town hall among data center workers won a reinstitution of COVID hazard pay. One petition won Raters millions of dollars per year in raises, and another won interns stipends for summer work.

AWU has started racking up majoritarian victories as well, surprising early leadership and actually shifting AWU’s strategic outlook. In 2022, Google Fiber retail workers in Kansas City won a recognition election 9-1, a monumental first recognition victory. The YouTube Music Operations team in Austin, Texas, got organized the same year, filed for recognition, and won 41-0. In a historic ruling, the NLRB affirmed Alphabet as a joint employer, after the YouTube workers staged a dramatic joint employment “wedding” between Cognizant, the contracting agency that employs them, and Google. The Google Help Content Creation team, jointly employed by Google and Accenture, followed in 2023, winning their recognition 26-2. Workers in these units will bargain for separate contracts.

Unfair labor practice charges have won workers their jobs back, and have provided key victories in recognition campaigns as well. In addition to majority legal strategies, a majority strike threat in 2022 won Google Maps workers a work-from-home extension.

We have taken a multi-pronged and somewhat ad hoc strategic approach, making use of different strategies and tactics that fit the many heterogeneous situations in which we organize.

AWU is pursuing broader campaigns challenging company-wide policies in addition to the smaller campaigns in specific corners of the corporation, though these have been less successful. AWU’s Every Google Worker campaign emphasizes the two tier workforce structure. As it was conceived, this campaign allows AWU to organize around solidarity as an issue, front-and-center, which we see as a critical strategy in an environment with such a diversity of work experiences. AWU members have also been involved in campaigns such as No Tech for Apartheid and ongoing salary-sharing efforts across the company, but the connection with AWU is looser.

Strengths So Far

The strengths of AWU’s structure emphasize the strategic links between the wall-to-wall and pre-majority components of the model and demonstrate the power of AWU’s multi-pronged approach. The flexibility of the pre-majority structure has allowed AWU to be resourceful and strategic in our organizing efforts.

AWU’s structure supports a wide variety of organizing efforts, all across the company, all at once. AWU has been able to focus on areas that are strategic, either because workers are particularly keen to organize or because workers have a disproportionate amount of power due to their roles in the production process.

“The possibilities of what we could choose to do are so vast that we can make strategic choices about which parts of the company we should really focus on,” says Koul, though she admits that, while the victories among contractors’ units so far have been powerful, AWU hasn’t been able to fully make use of this strategic opportunity.

AWU has been able to focus on areas that are strategic, either because workers are particularly keen to organize or because workers have a disproportionate amount of power due to their roles in the production process.

That workers in every organizing effort across the company have AWU to support them has been immensely beneficial. “We have the flexibility to build up a broad base, find good opportunities in a formal way, in a structure that allows us to grow without the need to build from scratch each time, and that gives us the opportunity to figure out what’s next in six different places at once. … We don’t need to set up separate structures or tools. … It’s really possible to build in either strategic or high-energy places all at once,” explains Schmidt.

And each effort creates more institutional experience and knowledge; each effort gets a bit easier. All leaders I interviewed emphasize how much they, and AWU as a whole, have learned in the past three years. When I compare my memories of the frantic, disorganized, and grueling earlier organizing efforts, such as the responses to retaliation workers experienced after the walkout, to the methodical and patient efforts of today, the value of the pre-majority union structure is clear.

AWU has also benefited immensely from our corps of members who can support the strategic organizing above, despite not being situated in strategic work locations themselves. These members can make phone calls, do research, train and mentor newer organizers. Since all members also pay dues, these members’ dues support the staff organizers who are a critical part of AWU’s organizing capacity.

A union at Google might easily look inevitable in hindsight, but the wall-to-wall pre-majority model made what was otherwise impossible possible. AWU provides an example of worker organizing within Big Tech and is a symbol of resistance at a nexus of the tech industry.

And, in addition to the opportunity to organize in particularly promising places, whether because they are high energy or strategic, there is also benefit in the act of organizing across work areas. “In some ways, what we’re doing is not so much organizing everyone under the same roof, as much as it is creating a structure that creates easy connections between, in some cases, what are genuinely distinct groups,” says Koul.

She goes on: “I think that we can and have been able to leverage that in order to help other sectors of the workforce organize. … It is a way to be strategic. … An FTE has access to a director or a VP in a way that our members who are Raters don’t. … That kind of cross collaboration is useful and strategic for organizing, and it bolsters people’s sense of morale. People feel like, it’s not just me, the people around me care what’s happening in my workplace.”

There are both structural and emotional gains from this collaboration. Different workers have different powers that can be combined in powerful ways. As Koul emphasizes, FTEs have access to organizational power that TVCs do not; on the flip side, TVCs organizing has absolutely energized and inspired FTEs across the corporation, as mentioned earlier. And, organizing wall-to-wall makes it possible for workers across the company, as a group, to analyze how the company structure works and develop strategy accordingly.

“The biggest lesson is, look under your roof and see who’s in the shop; and maybe the thing that makes sense is for your particular job role to organize as your own unit; but the importance and value of having those cross connecting relationships and really truly being in solidarity together, and building up to a structure where you’re doing joint decision-making; you should always be thinking about those things.”

Perhaps beyond any other strengths of the wall-to-wall pre-majority structure is simply AWU’s existence. A union at Google might easily look inevitable in hindsight, but the wall-to-wall, pre-majority model made what was otherwise impossible possible. AWU provides an example of worker organizing within Big Tech and is a symbol of resistance at a nexus of the tech industry.

Challenges

The leaders I interviewed stressed first and foremost the challenge of focus. Organizing across such a large corporation, while exciting and providing the many opportunities discussed above, has challenged AWU to maintain clarity of both purpose and strategy.

“We’re trying to do too much,” says Koul. “The possible world of all the things you could focus on organizing is just enormous. And you have members from all over the place who want to focus on organizing in their neck of the woods. And so as an organization, how do you set priorities, and how do you say, we’re only going to work on these three things for the next year?”

The challenge of focus is exacerbated by having many different campaigns progressing at different phases: the whole union, with our various campaigns, can’t move together in lockstep, so creating coherent strategy is hard.

“The possible world of all the things you could focus on organizing is just enormous. And you have members from all over the place who want to focus on organizing in their neck of the woods. And so as an organization, how do you set priorities, and how do you say, we’re only going to work on these three things for the next year?”

Additionally, AWU has found it difficult to build solidarity across workers in very different work positions. “You actually have to forge solidarity through action and through organizing between different groups,” Koul emphasizes, “and it’s probably more harmful if you just call yourself wall-to-wall but then don’t actually structurally address some of those issues.”

AWU has sought more blue-collar workers, but Alphabet’s white-collar staff, especially engineers, remain overrepresented. The diversity of work roles is only part of the problem, though; it’s also just hard at the scale at which AWU is currently operating, and it will only get harder.

“Solidarity comes from shared understanding,” says Schmidt, “and building shared understanding is hard in an organization this size without really strong shared spaces.”

Some of these problems may have been less acute earlier in AWU’s history, when excitement around the group identity was fresher. “When we started, and we were 200 people in total, we had an easier time having a sense that we were all working together on things,” recounts Schmidt. “As we have grown, it has become harder for people to identify with … union-wide needs.”

That change in group identity over time points to the final organizational challenge AWU seems to be facing: sustainability. Any organizing effort ebbs and flows, but AWU’s structure may exacerbate these ebbs and flows. Koul worries that, over time, the organization might spread ourself too thinly, without the density necessary for sufficient power, and that could open up additional vulnerabilities.

“Solidarity comes from shared understanding, and building shared understanding is hard in an organization this size without really strong shared spaces.”

And aside from organizational issues, AWU is operating in a challenging context. The tech industry is notorious for its high turnover, and for a union that represents such a small portion of the workforce, where density is a long way off, keeping up with attrition has been and will continue to be a constant struggle. There is also a notorious lack of urgency felt among the highly privileged staff.

“Don’t let people fall into a hole of disconnecting, and avoid playing Model UN with rules and regulations as a way of getting people involved,” Schmidt cautions, “because the type of people who get and stay involved in that case are just not most effective at creating energy.” While this advice applies among any workforce, the engineers who make up the bulk of Google’s workforce seem particularly prone to falling into these traps.

Google has the “ability to trivially snap their fingers and destroy a thing.”

Finally, there is simply the raw power of the opposition: in this case, one of the most powerful megacorporations ever known to humanity. The path to power is not clear, and on the incremental path between here and there, Google has the “ability to trivially snap their fingers and destroy a thing,” Schmidt emphasizes, as it has done after unionization victories among YouTube workers and Raters.***

Power imbalances exist at any workplace, but at a megacorporation such as Google, the power imbalance is extreme. Even in the most favorable organizing conditions, with a clearly defined work unit that is structurally important to Google, management is still able to destroy the unionization effort by relocating the workers and/or the work, even if it costs them some in the short run.

Conclusion

AWU is a beacon for organizing at megacorporations, especially among headquarters staff and in a notoriously anti-union sector. While AWU continues to grow, amid a growing union movement across the American tech sector and the U.S. more generally, we will need to transition to more exponential growth if we are to fulfill our original vision of a wall-to-wall unionized Alphabet.

Nonetheless, AWU’s emergence from years of prior activism at Google and across the tech industry demonstrates the power of developing worker identity prior to a more formal organizing drive. Our multi-pronged and ad hoc strategic approach has presented challenges of focus and coherence, but has garnered a variety of majority and minority victories. AWU seems to be the best possibility for challenging Alphabet and its monstrous power, and exemplifies how workers might challenge other megacorporations as well.

Further Reading

“Now I Know My ABCs: A Conversation with Two Organizers from the Alphabet Workers Union.” 2021. Logic(s) Magazine 13 (May).

Redwine, Clarissa. 2021. “The ABC’s of Google’s New Union.” Collective Action in Tech.

Tarnoff, Ben. 2020. The Making of the Tech Worker Movement. Logic(s).

Tarnoff, Ben, and Nataliya Nedzhvetskaya. 2021. “The Making of the Tech Worker Movement: A 2021 Update.” Collective Action in Tech.

* Quotes and other material come from interviews with the author.

** AWU keeps most of its information off of Google platforms. While there is no conclusive evidence that Alphabet is monitoring personal communications of its workers, Alphabet certainly has the technical capability to do so, and Google’s privacy policy includes language about protecting against issues “that could harm Google.”

*** As of this writing, Google seems to be dropping entire Appen contracts just as it did with Cognizant after the YouTube workers victory.

Ike McCreery is an organizer, researcher, and engineer. They chaired the organizing and steering committees of the Alphabet Workers Union and were a founding member of Tech Workers Coalition Seattle. They worked as a senior site reliability engineer at Google.