During the height of the Great Depression, when jobs were scarce and mass layoffs were commonplace, the farm economy of the Jim Crow South collapsed. With starvation looming, poor white and Black Americans alike streamed into cities such as Atlanta hoping to find relief.

Of course, for Black Americans, the hardships of the Depression were compounded by the white supremacist social order of the Deep South. As the saying went, “last to hire, first to fire.” Many Black workers found it exceptionally difficult to find work as they were often overlooked in favor of their white counterparts. A Ku Klux Klan–affiliated group, “the American Fasciti Organization,” routinely marched through downtown Atlanta harassing Black residents and demanding that every Black worker be fired until all whites had jobs.

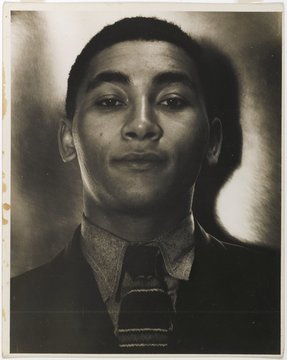

The Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) had sent activists into the Deep South since the inception of the Great Depression, attempting to both galvanize a multiracial labor movement and facilitate Black liberation from racial prejudice in the process. One such activist sent to Atlanta was a 19-year-old Black man from Ohio named Angelo Herndon.

Herndon, the son of a coal miner, worked as a laborer and miner under highly exploitative conditions as a teenager, sometimes working up to 11 hours a day. He became radicalized in the coal mines of Birmingham, Alabama, and joined the Communist Party, eventually ascending to the role of paid organizer. He went on to organize sharecroppers in Alabama and rallied support for the Scottsboro Boys. His experience in Atlanta however, solidified his renown as a civil rights and labor rights activist.

After arriving in Atlanta, Herndon wasted no time organizing a rally in front of the Fulton County Courthouse. On June 30, 1932, under the cover of darkness, Herndon distributed 10,000 fliers under the name “Unemployed Committee of Atlanta” to mailboxes across the city addressed to “Workers of Atlanta, Negro, and white.” Herndon successfully drew 400 Black and 150 white industrial workers, who crowded on the courthouse steps demanding help. Herndon led the demonstrators into the courthouse, where they waited outside the offices of the county commissioners.

After waiting for 30 minutes in the hallway, only the white workers were allowed to speak to the county commissioner, Walter Stewart. Nonetheless, the multiracial action stunned Fulton County officials who swiftly approved $6,000 in relief aid the next day. The money was collectively spent on groceries for the poor. He went on to further solicit Blacks and whites for membership in an integrated Communist Party of Atlanta.

Unfortunately, this was not the end of Herndon’s story in Atlanta. While checking his mailbox on the night of July 10, Herndon was arrested by two Atlanta detectives, who searched his home and found boxes full of communist literature. He was subsequently indicted for attempted insurrection. His case moved through the Georgia judicial system, and he appeared twice before the Supreme Court.

If convicted, he faced the electric chair. The Internal Labor Defense — the legal wing of CPUSA — hired two Black Atlanta attorneys, Benjamin Davis Jr. and John Geer to defend him. When Herndon was called to the stand, he used the opportunity to address the ruling class’s strategy of dividing working-class Black and white communities to prevent multiracial solidarity.

“In order for the white workers to get relief,” he said, “and in order for the negro workers to get relief, they both will have to get together and forget about the question of racial discrimination, forget about this question of white skin and black skin, because both are starving, and the capitalistic class will continue to prey on this tune of racial discrimination.”

He was found guilty — but through a series of appeals was eventually released, after spending 33 months in Fulton County jail.

The multiracial solidarity movement Herndon spurred is reflected in current union efforts across the country, like the Amazon union drive in Staten Island last year. White supremacy, and the enforcement of racial division, have remained a central pillar of capitalism. Unity and diversity are our strengths. Once we understand the commonality of exploitation faced by white and Black working-class communities under capitalism, we can begin the process of reconciliation and unity, under the banner of socialism.

Sources:

- Beasley, David. A Life in Red: A Story of Forbidden Love, the Great Depression, and the Communist Fight for a Black Nation in the Deep South. John F Blair Pub, 2015.

- Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950. W. W. Norton & Company, 2009.

- “Herndon, Angelo.” Encyclopedia.Com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/african-american-focus/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/herndon-angelo. Accessed 15 Dec. 2022.