In the Great Resignation, millions of workers are quitting, but they could use assistance to organize for power in the workplace and improve their jobs instead, argues Eric Dirnbach. Image via Facebook / Rachael Flores.

The “Great Resignation”

There is a lot of news these days about the “Great Resignation” – millions of workers are quitting their jobs. Moreover, there is much hand-wringing in employer circles about a labor shortage and trouble finding workers, especially for lower wage jobs. Anecdotally, we’re seeing photos and videos online about workers quitting – with signs posted at McDonalds, Burger King, Dollar General, and Family Dollar, and videos of workers quitting at IHOP, McDonalds and Walmart.

The data does back this up. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has data from their Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) which looks at the number of workers who quit and are laid off each month. BLS defines these terms as:

Quits are generally voluntary separations initiated by the employee. Therefore, the quits rate can serve as a measure of workers’ willingness or ability to leave jobs. Layoffs and discharges are involuntary separations initiated by the employer.

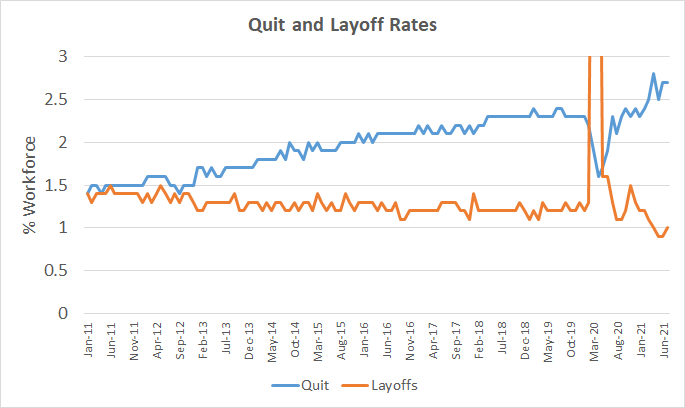

So looking at the relative amounts of quits and layoffs can show whether workers or employers feel they have more leverage.

BLS press releases from the last three months where there is data, May, June and July 2021, show that about 11.5 million workers quit their jobs, whereas in this timeframe, employers laid off only 4.5 million. Here is a chart below showing the percentage of all employed workers quitting and being laid off each month. We can see an increase in quits after the dip when the pandemic started, and a decrease in layoffs after the pandemic spike. The layoff spike reached over 8%, which I’m not showing in order to see the other data more clearly. The average quit rate over the last three months has been 2.6%, while the layoff rate has been much less at 0.9%. So it seems that workers feel much more empowered to quit, and employers are more reluctant to layoff workers.

Also regarding the trends throughout the last decade, it makes sense that worker quit rates were gradually increasing while layoff rates decreased a bit, because the unemployment rate fell throughout this time after the Great Recession from about 9% at the beginning of 2011 to a pre-pandemic rate of 3.5%. When unemployment is low, employers tend to hold onto workers and workers feel more free to quit.

Why is this Happening?

Conservatives have been clutching their pearls at the thought that government pandemic assistance has encouraged workers to stay home. It’s certainly much more complicated – there are issues of childcare, school closures, and many workers are justifiably scared to go back to work during a pandemic that’s still raging. The jobs with the largest mortality rate increase during the pandemic have been cooks, warehouse workers, agricultural workers, bakers and construction laborers.

But perhaps the assistance has to some extent helped workers stay home, and that’s a good thing. A major goal of the assistance should be to help workers while large sections of the economy had to shut down because of the pandemic. And we should absolutely support any help that allows workers to avoid terrible jobs. But now that pandemic assistance is winding down, employers hope that workers will come back to work. Sometimes right-wing folks who want to coerce workers back to work say the quiet part out loud.

But not so fast, because the pandemic may be leading to a major shift in how workers think about work. Millions of workers who were able to work from home are wondering why that can’t continue. A recent survey found that “almost 40% of workers—and 49% of those who are millennial and Gen Z—said they’d consider quitting if their employer didn’t let them work remotely at least part of the time.”

Tens of millions of employed workers are unhappy with their jobs. One survey found that “About one-third of workers are thinking about quitting their jobs, while almost 60% are rethinking their career at least somewhat.” Another found that “55% of American adults are planning to switch jobs,” with even higher levels among Gen Z and Millennials.

Furthermore, millions of “essential” workers that had to show up every day during the pandemic have had to deal with tremendous risk and stress at work, while their employers often fought measures that could ensure their safety. They are tired and burned out and want more.

What’s the Impact of Mass Quitting?

An increase in quitting and workers being picky about jobs can have an impact, as employers have had to raise wages to attract workers in an economy scrambled by the pandemic. Last month the average wage for restaurant and grocery workers went above $15/hr for the first time ever. Where the “Fight for $15” was aspirational when it launched in 2012, it’s now a reality for most workers, with 80% making at least that wage, and “Job sites and recruiting firms say many job seekers won’t even consider jobs that pay less than $15 anymore. For years, low-paid workers fought to make at least that much. Now it has effectively become the new baseline.” We shouldn’t feel bad for the bosses though, as average pay has been lagging far behind productivity increases for 40 years.

But Workers Should Be Organizing

However, we have to say that workers quitting leaves a lot of power, money and other potential improvements on the table. If employers are desperate for workers, then workers also have the leverage to organize for better conditions in the jobs they have. After all, millions of workers quitting bad jobs generally leaves them seeking other jobs that are just as bad. Rather than workers playing a massive game of musical chairs in the job market, the working class would be in a much stronger position to make gains through organizing unions at their current jobs on a large scale.

The annual Gallup union approval survey has recently recorded a modern record approval rating of 68%, the highest level since 1965. A major survey showed that about 50% of non-union workers want to join a union, which considering the private sector is 50 million workers. So the massive interest in joining unions is out there.

But most workers likely don’t have a clear idea of how that can happen. Organizing a union is not something that most workers think of when they have problems at work. More importantly, most don’t know that they themselves have the ability to form a union right now in their workplace. Any group of workers that comes together in “concerted activity” to improve working conditions can be considered a union, even without formal recognition and a written contract. This is where a major intervention by the labor movement in worker organizing training and education can have a massive impact.

Unions Must Expand Their Organizing Training

The labor movement overall is not organizing enough workers. As an example, there were only 827 NLRB elections last year, with about 51,000 workers voting, and the trend in recent decades has been fewer elections and workers organized nearly every year. With this rate of organizing, it would take 1,000 years to reach all the workers who want to be in a union.

Unions as they currently operate don’t consider that they have the capacity to reach the millions of workers who could use organizing help. So it’s critical for unions and other groups to create new ways to provide organizing training and assistance to more workers on a much larger scale. And they should support these workers even if they organize in non-traditional ways, by simply fighting for better conditions, and don’t seek to get formal recognition or contracts.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) has perhaps the best organizing training program, uniquely open to all workers, and it should find ways to scale up. A project launched at the beginning of the pandemic last year by the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and the United Electrical workers union, the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC), has worked with thousands of workers, and is a model for how unions could open up their training to more workers who need it, as I have discussed in more detail. Unions can adapt these models or create other groups to provide this kind of training.

In the U.S. labor movement, we often wonder when the next upsurge era of unionization will happen, as it did in the private sector in the 1930s and the public sector in the 1960s. When will we see a time when millions of workers are fed up with the status quo, and most importantly, want to do something about it? We may be in that era again, and the labor movement must seize this moment.

Eric Dirnbach is a labor movement researcher, activist, campaigner, organizer, educator, writer & socialist, based in New York City.

This article is also published in Organizing Work.