Meet an EWOC organizer who helped organize Barboncino and Nitehawk and moves at the “speed of trust.”

The Dam Breaks

In June 2022, a sewage pipe exploded in the basement of Barboncino Pizzeria in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood. This caused a catastrophic flood within the restaurant in the middle of a busy service. Management forced workers to leave the floor upstairs in the dining area and start bailing out the sewage runoff. Workers had to vacuum and dispose of toilet paper, feminine hygiene products, and sewage water.

When they had finally cleaned up the toxic mess, they were covered in filth and expected their manager to let them go home. The owner of Barboncino told the manager that if workers went home, he would consider it “a mutinous act.”

And so, the workers walked off the job.

For Alex Dinndorf and his co-workers at Barboncino Pizzeria, this was the last straw. Alex’s roommate Mike was one of those workers responsible for bailing out the sewage. “I could smell it all the way from the second floor,” said Alex. He vividly remembers the stench from Mike’s clothing the minute he walked into the vestibule of their four-story apartment building.

From Twin Cities to NYC

Originally from the Minneapolis metro area, Alex is a veteran of the food service and restaurant industries. His first job at age 15 was at a McDonald’s. His first union job at age 17 was in a deli at Cub Foods, a large regional grocery chain in Minneapolis. Alex prepared food, carving and slicing meat — one of the “dirtier jobs” in the grocery store, which came with a membership in the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW) local.

“I didn’t know anything about unions at the time,” said Alex. “I was just a kid, but I remember even as a high school student thinking that I made a little bit more than some of my friends made with this union job.”

At 18, Alex moved to New York City and worked in more restaurants there. He recalls that this was a turning point for him. “I lived with seven roommates in Crown Heights. My rent at the time was $800 a month and my wage in 2016 was $9 an hour. It was awful.”

Radicalizing on the Line

After years of working abysmal jobs in terrible kitchens as a line cook and a dishwasher, fast food and grocery stores, Alex declares, “I became politically radicalized working in places like this.” Intimately familiar with the raucous, chaotic, and at times dangerous working conditions that are emblematic of restaurants, Alex describes the kinds of working conditions that food services workers have had to endure.

“People are working with knives and they’re yelling at each other, swearing,” he said. “They get burned and hurt all the time. You’re working until 2:00 in the morning, and your boss might be drunk. There’s rampant abuse and misconduct and sexual harassment. Everyone who works in the food service industry, especially over many years, starts to see how unregulated it is. It’s like the Wild West.”

Barboncino was not unique. There were numerous examples of scheduling problems and unjust disciplinary treatment. “You say something that the manager doesn’t like, or you stand up for yourself, and you can get fired just like that,” he said.

There were also simple things that made working conditions intolerable over time. For example, when Barboncino was ridiculously low on forks for two months, bussers had to run down silverware constantly. Something like this would be an easy fix, but the owners were not interested in equipping their workers to operate efficiently.

An Historic Union at Barboncino

Until that infamous night, which Alex and his friends euphemistically dubbed “poop night,” workers at Barboncino had only casually thrown around the possibility of forming a union. Alex had been inspired by the Starbucks Workers United campaign of smaller unionized shops popping up all over the country during the pandemic.

“I started to think that maybe it’d be interesting if I worked at a unionized restaurant,” he said. Brendan, another Barboncino co-worker and close friend, had been involved with New York City DSA, which had connections with EWOC.

Although the owner told the workers that night that he’d fire them for not completing their shifts, the manager had covered for them, and the situation blew over as far as the owner was concerned. Workers, on the other hand, knew that things needed to change. Alex and his friends decided, “Let’s actually call somebody and do this thing.”

Working with EWOC

Brendan reached out to EWOC, who paired them with Andrew Stando, a veteran EWOC organizer. This was Alex’s introduction to the EWOC organizing model. Being educated and trained by Andrew as a worker, Alex learned practically what it meant to build a union and how realistic and approachable it was.

“Andrew was an incredibly dedicated EWOC representative,” said Alex. “He started going to our meetings and giving us counsel right away. He was very much a classic organizer, listening 75% of the time, speaking 25% of the time, and from there we started to learn how to organize.”

Andrew has become a close mentor and friend to Alex through this process. As for the rest of the workers at Barboncino, Alex reveals that getting them on board happened quite naturally.

“Once people understood what a union was, they wanted one,” he said. Alex and his co-workers educated themselves about their Weingarten rights and progressive ideas that could be incorporated in the contract. They learned that a contract could protect them from being over-scheduled, prevent sexual harassment, and provide a living wage. They reflected on what it could actually mean to have regular hours and strong disciplinary protections.

Winning the Barboncino Union

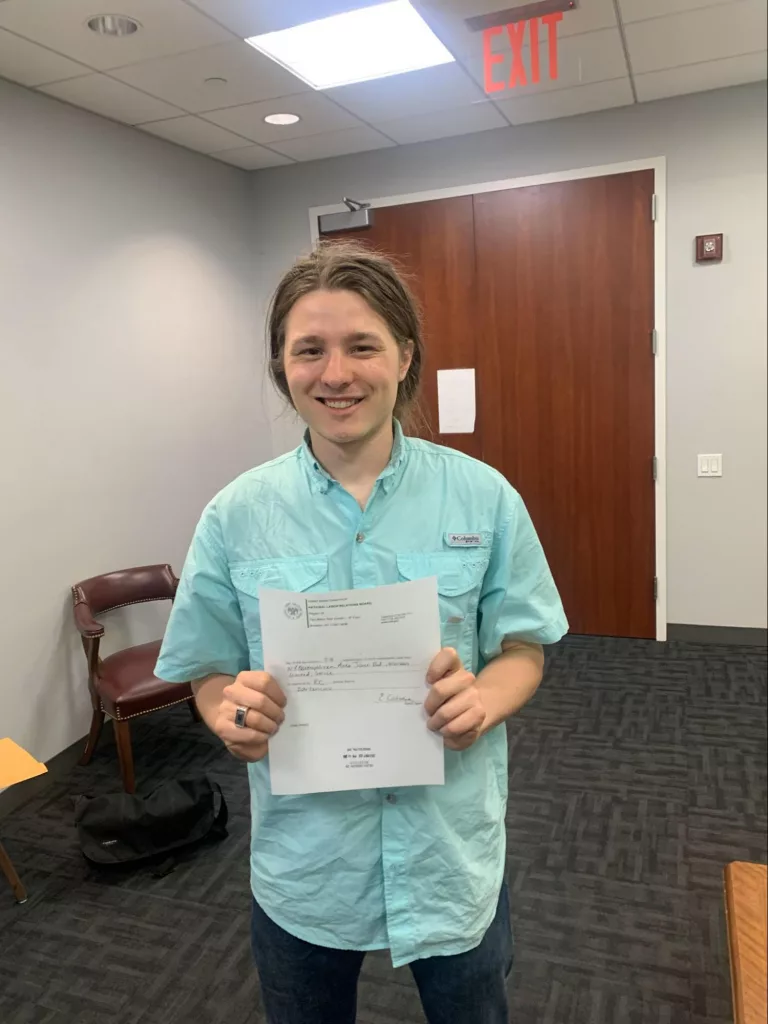

Barboncino Workers United won their election in July 2023, approximately one year and one month after that unforgettable night when their boss forced them to work in unsafe, unsanitary conditions and became the first unionized pizzeria in NYC. The experience of building a union with his best friends left Alex with a desire to get more seriously involved in the labor movement. Almost immediately, he joined EWOC as a volunteer organizer.

Alex had a vision to build Barboncino into this progressive idea of what a restaurant could be. Since it was the first unionized pizzeria in NYC, he wanted to create a blueprint to bring unions to all food and beverage workers one shop at a time.

In January, Alex attended the “Inside Organizer School” and met Richard Bensinger, who advised him that, “grandiosity is an excuse for laziness.” This left an impression on Alex. With those sobering words as a guide, Alex recognizes that organizing the service industry happens one shop at a time, worker to worker.

Follow Barboncino Workers United (@barboncionworkersunited) on X/Twitter and Instagram

The Barbenheimer Effect

The media buzz surrounding Barboncino Workers United during the summer of 2023 intrigued workers at Nitehawk Theater. They had just endured a difficult summer due to the popularity of ticket sales from “Barbenheimer,” wherein two blockbuster movies, “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” were released as a double feature. The sudden flood of customer traffic brought to stark light the problems that had always been there of overscheduling, low pay, and unsafe working conditions.

Nitehawk is a dinner theater in Prospect Park that offers drinks and refreshments to customers while they enjoy a movie in a dark theater. The uniquely complex and challenging working conditions at Nitehawk were notorious in Brooklyn. The theater requires a variety of staff, from cooks to bartenders to food servers, to provide these concierge services. Food runners wear earpieces while discreetly navigating a network of weaving stairs, in and out of seven different theater screens within a 100 year-old building.

The owners at Nitehawk were ecstatic that Nitehawk Prospect Park was one of the highest grossing movie theaters in the country that summer. They convened a meeting with their staff to boast about their success with little acknowledgement of the hardships that workers faced.

After the workers at Nitehawk reached out, Alex supported their intake. He joined their earliest meetings and helped to connect them with UAW local 2179. There was a lesson to be learned about the difference between organizing his own workplace at Barboncino and organizing Nitehawk. Alex realized that once he was no longer a worker, he could not exert influence on the shop floor, where the organizing conversations were happening. “You can give workers advice, but at the end of the day, all the power in the shop comes from rank and file,” he said.

Follow the Nitehawk Workers Union (@nitehawkunion) on X/Twitter and Instagram

“Build strong, not fast”

Alex works closely with Will, who is the UAW representative, and expresses that it’s very much a partnership between EWOC and the UAW. Alex feels strongly that an incredibly dedicated volunteer organizer is what builds success in these campaigns. Just as Andrew Stando supported, trained, and modeled the type of dedicated EWOC volunteer organizer that Alex aspires to be, Alex finds fulfillment in doing the same.

“I go to every single organizing committee meeting,” he declares. “I’m in the group chats and supporting the workers anyway I can.” Alex often connects with the other food service workers who are organizing in NYC, even if they’re with different unions or brand workers. “A big part of the scene is just checking in and saying hi and making yourself available,” he said.

Alex encourages workers, “to build strong, not fast. A key lesson that I’ve learned is that organizing moves at the speed of trust. Everything is about relationships, asking for updates, and establishing rapport. And for people who want to organize service workers specifically, it’s important to be prompt, respond quickly to someone who needs help, and don’t be a stranger.”

Personal Growth

Being an EWOC volunteer organizer also has personal significance for Alex. “Working in these places my entire life,” he said, “being exploited and undermined, working at McDonald’s, working saute, as a fry cook, as a line cook, doing all of these laborious jobs for terrible wages, I felt like it was a chance to fight back.”

A graduate of Hunter College with a degree in english and political science, Alex had at one time considered becoming a librarian due to his love of books and reading. Today, he regards his vision for a powerful and growing labor movement as his labor of love.

“I always feel better after I do organizing work,” he said. “Even if I’m having a bad day, or if I want to just do nothing, I’ll send a useful e-mail or send somebody the right contact information or have a phone call, and I always feel better.”

Alex’s message to other food service workers: “There are so many reasons why you should organize!” Alex hopes to galvanize other workers in the food service and restaurant industries to unionize.

The Future of Organizing

“The Barboncino model, now the Nitehawk model, proves that you can unionize a restaurant and you could also unionize a giant in the restaurant industry,” he said. “Even if you don’t have organizing experience, and you feel like you can’t organize your own shop. Start with a base, think locally and contact EWOC support. If you’re looking for a job, there are plenty of campaigns that could use young, ambitious left-wing workers, just let me know!”

Thinking back on his own evolution, Alex counsels young people who feel black-pilled or fatalistic to become a part of a political project that they really believe in. “It’s a ton of work, and I’ve made sacrifices to put workers first,” he said. “But I love it. I wouldn’t want to do anything else.”

Workers United recently hired Alex Dinndorf as a part-time organizer. He is involved with campaigns in New York City and remotely around the country and still very much involved with organizing restaurant workers, including another restaurant campaign in Brooklyn.

If you’d like to connect with Alex, he can be reached at [email protected].