Appalachian coal mines in the 1910s were crucibles of corporate exploitation. Mine workers were isolated in unincorporated “company towns,” many of which were ringed with Gatling- and machine-gun towers. They lived in squalid corporate housing, often little more than shacks just steps from the mines in which they worked. They had no local government or local voting rights, nor did they possess any First Amendment rights within the corporate compound: their mail was screened and stolen, and their political speech was silenced.

Any violation was punished with immediate firing and eviction. Rather than dollars, miners were frequently paid in “scrip” — worthless outside the company towns. Fired miners and their families often faced bleak economic odds, something their employers were only too happy to take advantage of.

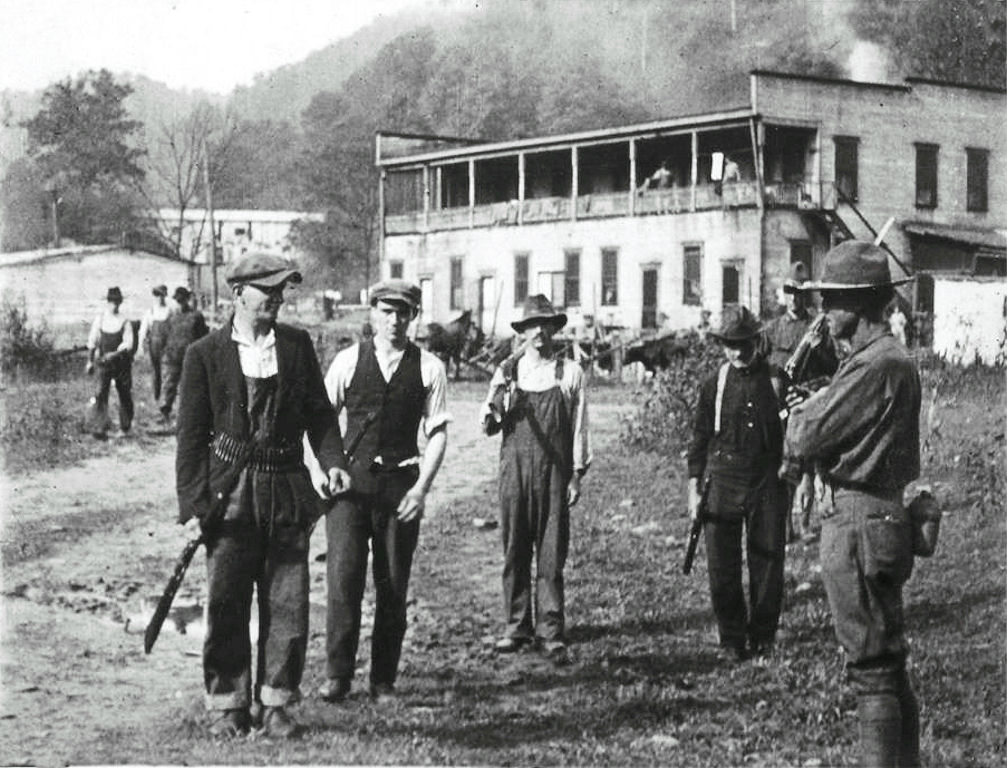

In 1920, workers began a major unionization push in the region, and thousands in mine-heavy Mingo County, West Virginia, voted to unionize. The companies fired them all, then hired corporate strikebreakers — recently responsible for a machine-gun massacre of striking workers in Colorado — to evict the vast majority. The resulting violence culminated in the declaration of “martial law” in Mingo County. Hundreds of miners were imprisoned. When labor leaders asked the governor to intervene, they were rebuffed. This led to the Battle of Blair Mountain.

The Battle of Blair Mountain

Over 10,000 miners amassed to march on Mingo County to free the workers imprisoned under martial law. To get there, they had to pass over Blair Mountain in neighboring Logan County. But the sheriff of Logan County was rabidly anti-union, and he amassed the largest private force in U.S. history to block them: 2,000 anti-union shock troops, financed by the coal industry, who were joined by nearly 1,000 public law enforcement officers. For more than a week, private corporate soldiers — not just unimpeded but assisted by local authorities — used bombs, rifles, and machine guns to stop the miners’ march. They used private biplanes to drop improvised barrel bombs on the miners and National Guard planes to spy on their positions.

The fighting ended when the president dispatched federal troops, and the miners, many of whom were veterans, surrendered rather than firing on them. In the months and years that followed, hundreds of individuals who had participated on the side of the miners were indicted and tried for treason. Many were acquitted by sympathetic juries. But the overwhelming feeling after the Battle of Blair Mountain was that of defeat: the miners never made it to Mingo County, over a dozen of them were dead, and hundreds had been harassed with bogus criminal charges. Interest in and support for unionization tanked.

The National Labor Relations Act

The effort to unionize West Virginia coal country did not resume until more than a decade later in 1935. But organizers stepped back into the breach with a powerful new weapon: the Wagner Act (also known as the National Labor Relations Act). While the Battle of Blair Mountain ended in a crushing defeat, the vicious suppression of miners set the stage for crucial advancements in workers’ rights.

The sheer brutality of what became known as the West Virginia Mine Wars shocked the public conscience. The spectacular display of corporate exploitation and abuse drove public interest in and support for federal labor laws capable of restoring industrial peace by empowering workers to resist the cruel excesses of capitalist greed.

Lessons from West Virginia

The Battle of Blair Mountain is an illustration of the savage lengths to which capital — aided and abetted by sympathetic public officials — will go to exploit labor. Back then, it was barrel bombs dropped from airplanes; today, it’s cartoonish arch-capitalists laughing and preening over the striking workers they illegally fired. It’s the same cruel indifference, and it’s the reason we have to fight to change anything.

The rights the Wagner Act enshrined in federal law — to form, join, or assist a union; to strike, picket, and protest; and to engage in concerted activity even without a union — are as raw and essential today as they were in 1921, and they go straight to the heart of what the West Virginia miners physically fought for at the Battle of Blair Mountain. That fight was one of countless in the decades preceding the Wagner Act, to say nothing of the political, philosophical, and spiritual fights waged over the same period in communities across the country.

Our labor laws are the product of strife and faith and tremendous, sustained effort. They were not given; they were taken. The rights we have now are the rights our labor ancestors fought for. And the rights we fight for now are the rights our labor descendants will have.